Potholes in South Street

This story is a series of reflections by John White, long-term resident of Battery Point and previous President of the Battery Point Progress Association. Another story by John can be found here.

The Battery Point Progress Association (BPPA) was formed in 1948 to work with the Hobart City Council (HCC) to fix potholes in South Street, which were said to be large enough to swallow a horse and cart. In those days South Street, McGregor Street and Kelly Street were dirt roads.

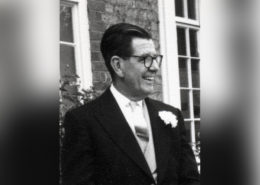

The first President of the Battery Point Progress Association was my father Alfred John White (pictured in the photograph for this story). He was in the State Government from 1942 for 17 years. He was a Labor minister for 13 years and served as Chief Secretary among other portfolios. He retired in 1959 from the Parliament to take the position of Agent General in London. The park at the bottom of Finlay Street was named after him. He was knighted in 1972.

Most of the workers houses in Battery Point were without bathrooms so they had ‘dunnies’ out the back. There was overcrowding of small houses with large families. The night cart came almost every night and the woodpile was next to the dunny. When someone went to the toilet, it was expected that he or she would bring wood back in for the stove and the fire. Saturday was bath night. The galvanised bath was placed in the lean to beside the kitchen. There was an order for the bath. Dad went first, followed by mother and the girls. The boys were last.

Battery Point was a close-knit village; there were almost no cars. Most workers were men who worked as waterside workers and in the slipyards, especially the Purdon and Featherstone Slip. Most of these men were related in one way or another. The waterside workers were reputed to be thieves. They were alleged to have long sticks with a hook on the end because every open porthole was seen as an opportunity to acquire some of the cargo! The story was told that when the Captain of an apple boat was getting changed, he noticed a hang point for his jacket and as soon as he hung the jacket up, it disappeared out of the porthole!

There was a general store in Montpelier Retreat and the proprietress was said to be a ‘fence’ – she bought and sold stolen goods. Montpelier Retreat was higgledy-piggledy with old houses on both sides. It would have made a worthy entrance to Battery Point, except that developers came in and more or less destroyed it. Replaced with the eyesore of concrete bricks on the south side, the northern side is an empty car park.

‘Joe the Junk’ was a store in Salamanca Place, where the Ball and Chain restaurant is situated now. Joe didn’t ask questions about where goods came from. I sold him a very nice navy blue three-piece suit that I had worn on a return trip from England for two pounds. It cost my parents 25 pounds in 1964!

The women who lived on Battery Point were seasonal workers at the jam factories in Salamanca or Hunter Street, working for J. G. Turners, Peacocks and Huoncry, or in Hunter Street for IXL.

There were two butcher shops in Hampden Road: McMillan’s, where Jackman and McRoss is now next door to the original Cripps Bakery and Nichols, which was where Da Angelo’s is now. The shoe shop, Connors, later to be the Wild Goose Nightclub (now demolished), was in the car park of the Prince of Wales Hotel, next to Da Angelo’s.

Once, aged about six, I went to Nichols butcher shop with my father. Mr Nichols said, ‘I’ve been given a message that the Health Inspectors are coming around to inspect the premises. Alfie, help me stamp some sawdust into the rat holes in the floor!” Dad was then acting Minister for Health as ‘Spot’ Turnbull, the Minister, had been stood down for an indiscretion. Dad grabbed me and rushed me out the door.

Mr. Kingston was the grocer on the corner of Hampden Road and Francis Street, now Kathmandu, with the curved door. You could get a paper bag of broken biscuits from the biscuit barrel for one penny!

There were two dairies – one in Hampden Road and the other on the corner of Colville Street and St Georges Terrace. There were numerous greengrocers, including general grocers, Ketchells, on the corner of Arthur Circus and Hamdpen Road. Mrs. Ketchell was profoundly deaf and she would lip read, self-taught. As children, we would go in with a message from my mother and read the note keeping our lips still. Mrs. Ketchell would try to guess the goods we needed to collect. We thought it was very funny. Now I think of it, it was actually ‘bullying’. When my parents found out, we were sent back to apologise. My mother wrote a note to Mrs. Ketchell apologising, asking forgiveness for us. I was grateful that Mrs. Ketchell didn’t put the note in the window.

A ‘Rabbitoh‘ did his rounds in a horse and cart, ringing his bell as did the milkman. While the milkman did his deliveries, you had to put a billy out and the milkman was expected to pour milk into it. The horse ‘Dubbin’ plodded up the street, stopping at the each customer’s house. The proud owners of new houses in Battery Point, especially when the Secheron Farm was being subdivided, were trying to get gardens started so kids were sent to pick up the horse droppings for the roses.

There were streets of merchants’ houses, such as Mona Street and south Clarke Avenue and workers cottages bounded by Kelly Street and Runnymede Street and Hampden Road and near the Slipyards.

The whole of Secheron Farm was offered to HCC for a park in 1922, but the HCC refused. Now they want to build a walkway from Marieville Esplanade to CSIRO, estimated cost $50 million!

Albuera Street High School, where the apartments are now, was the local school for Battery Point children and it became overcrowded. There was another school opposite Bob and Toms Service Station, on the corner of Hampden Road and Sandy Bay Road, which burnt down.

The first argument about the Battery Point Community Centre took place in the 1950s. An entrepreneur wanted to buy the Methodist Chapel, where Miss Henslowe ran a Sunday School with a tight rein, and convert it to a service station. Miss Henslowe went with a deputation of Methodists to the Chief Secretary A J White, who organised a loan to the Sunday School Committee for 3000 Pounds (in those days a considerable sum). It included 1000 Pounds from the Government, 1000 Pounds from the HCC and a loan from the St. Georges Parish.

Miss Henslowe was very conservative. She was very grateful for the loan, but the deputation resented going to the Labor Government with a ‘begging bowl’. It was still in the days where there was religious bigotry. There was public outcry. ‘What did the Chief Secretary know about retailing petrol?’ But the Community Centre was saved!

Next was the fight over Narryna. The Premier at the time, Robert Cosgrove, had a view that Battery Point was a slum and should be demolished. Narryna in Hampden Road was due to be demolished for a carpenter’s factory, to provide work for the locals in the area. A J White opposed this and said to the Premier, ‘Over the road you have the Queen Alexandra Hospital (the Hobart Maternity Hospital, now the apartments). What will l do when the women complain to their husbands about saws starting up at dawn? I will send everyone who complains to me about the noise to you!’

Opposite the Hospital, on the corner of Stowell Ave and Hampden Road, was Bahrs chocolate shop, now proposed as a restaurant. It was here that the relatives bought the chocolates for the new mums.

In Stowell Ave, there was a Commonwealth Hospital, now apartments. There were some significant health issues. There was an outbreak of poliomyelitis in 1937 and 1938 – 421 people per 100,000 contracted the disease – making it one of the worst outbreaks in the world. 81 people died. The road to Launceston was closed in the Midlands to stop the disease spreading. There were people in Battery Point who were crippled and some died. The Government rushed in the new Salk vaccination. I got it by injection at school at St. Virgil’s in 1954.

1 DeWitt Street was the Battery Point Police Station. One day, Constable Yost seized my football when my gang of friends and I kicked it over fences in Clarke Avenue. We were at fault. We kids could not kick straight and the owner of Secheron House had seized the football. My Father told me to ask Constable Yost for it back. I went the local ‘cop shop’ in fear and trepidation. I knocked on the door and waited for Constable Yost to come to the door. He opened it. He was big, with a huge pot belly, heavy boots, braces and a belt. He said, ‘You are causing me worry!’ He kept me waiting while he got the football. I was 10 at time. He handed me the football and when I turned to go out the gate, he kicked in me the bottom! It was so forceful it carried me to the footpath. Mr Yost said, ‘that’s a lesson for you. Learn to kick straight.” I didn’t tell my father about the kick in the backside. I learnt years later that my father was a friend of Constable Yost.

There was a Battery Point bus from Franklin Square. The route was around Castray Esplanade, and into Hampden Road and there was a stop on every corner in Colville Street. The Terminus was at the corner of Colville Street and St. Georges Terrace.